Research paper by Erika Stauffer

It would be a marvel if Latter-day Saints did not love speculative fiction.

In his book People of Paradox: A History of Mormon Culture, Terryl L. Givens accepts this statement by an internet news article with hardly a statistic, attributing this fact to the prominence of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the state of Utah (p. 320). Apparently, it is so obvious that Latter-day Saints love speculative fiction that no evidence is needed.It may be the culture. It may be religion or the landscape. Maybe it’s something in the water. Whatever the reason, Utah has some of the nation’s most prolific producers and ravenous readers of science fiction and fantasy, known in the book world as “speculative fiction.” (Religion News Blog)

Many sources—scholarly and not-so-scholarly alike—have proposed answers to why this passion exists. With the aid of reason and research, I would outline three explanations that overarchingly capture why Latter-day Saints love speculative fiction.

- Speculative fiction resolves conflicting taboos.

- Speculative fiction is a theologically-consistent alternative to Modernism.

- Speculative fiction’s suspension of disbelief is required to keep up with Latter-day Saint theology in the real world.

1: Speculative Fiction Resolves Conflicting Taboos

Over the decades, several early leaders of the Church have professed that “We will yet have Miltons and Shakespeares of our own” (Whitney, par. 18; see also “Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects”). And why not? Orson F. Whitney, a to-be Apostle of the Church, stated, “Our literature must live and breathe for itself. Our mission is diverse from all others; our literature must also be” (par. 17), and Harold Bloom asserts “nothing else in all of American history strikes me as materia poetica equal to the early Mormons, to Joseph Smith” (Givens, p. 287, italics in original). It does not take much insight for Givens to note, “Almost everyone who has assessed the field of LDS literature has cited the epic qualities of the Mormon story” (p. 287).

However, Givens also notes that those epic qualities have not been fully exploited:

“For the most part, . . . the first decades of the twentieth century saw an efflorescence of short stories, but no flowering of work equal to the richness of Mormon theology or, more surprisingly perhaps, even approaching the sweep and grandeur of its founding history” (p. 287).

When there is clearly such substantive and intriguing material, what could be holding the immense potential of the LDS literary tradition at bay?

Pressure regarding what to write can come from two directions: without and within. LDS authors find themselves confronting two taboos that make it equally difficult to show up in the public sphere as to provide quality in the private sphere.

Fear of Negative External Opinion

From without, the first taboo is against religion and spirituality. Modern American culture makes it difficult to open public discussions about religion, let alone a radical religion like the one Latter-day Saints have—unless, of course, that religion is being condemned. The result is that overtly-LDS content avoids the public sphere, appearing more prominently within LDS-only circles.

Unfortunately, a permeating fear in LDS culture—that of attracting negative public opinion—amplifies this external taboo. When I heard that a prominent LDS publishing house originally did not publish speculative fiction, I reached out to ask why. However, I was unable to convince the publishing director that my question had no ill intent: they were so terrified of being viewed in a negative light that, instead of answering my question, their emails sounded like sales pitches, assuring me that they had opened their doors to fantasy as soon as a customer survey revealed that Harry Potter was incredibly popular.

Given the history of abuse the Church has faced, this fear before the public eye makes sense, although it remains inconsistent with the Church’s theology. The Bible does teach to “abstain from all appearance of evil” (1 Thessalonians 5:22, KJV), but Jesus certainly did not fear the violent clashes between His truths and what contemporary culture labeled an “appearance of evil.”

In reference to one of those public-opinion–based appearances, LDS-author Shannon Hale has noted, “With a lot of conservative religions—and Mormonism would definitely qualify—there is a taboo against fantasy concepts, against magic” (Paulson, par. 15). When we consider together the taught fear of negative public opinion that permeates LDS culture and this latter societal taboo, perhaps the publishing director’s fear was itself the answer to my question.

Thus, LDS’s culture’s theologically-inconsistent fear of “all appearance of evil” in the public eye internally reinforces the taboo against religion in American culture, preventing overly-LDS literature from reaching the public sphere.

Fear of Negative Internal Opinion

Meanwhile, the fear of “all appearance of evil” sits differently inside Latter-day Saint culture: when among their own people, this fear puts an internal taboo behind a call for strict orthodoxy.

Eugene England notes, “everyone wants literature that is uniquely Mormon, even ‘orthodox’—but also good, that is, skillful and artful.” However, England continues, “the problem is that focusing on either quality seems to destroy the other” (Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects, par. 11).

Edward A. Geary gives a plain explanation for this apparent incompatibility:

Good fiction is seldom written to ideological specifications. It is one thing to ask the artist to put his religious duties before his literary vocation or to write from his deepest convictions. It is quite another to insist that he create from a base in dogma rather than a base in experience. (p. 16)

The result is that, as LDS writers attempt to build their literature on a foundation of doctrine, the human experiences that create good literature fall by the wayside—orthodoxy without quality. Meanwhile, LDS writers who attempt to put their experiences first discover, as Orson Scott Card has, that “my works will always reveal my beliefs, both orthodox and unwitting heretical” (Card, p. 12)—quality without absolute orthodoxy.

Unfortunately, absolute orthodoxy is what LDS culture (again, not doctrine) calls for. Card noted about this phenomenon,

LDS readers who natter about . . . my failure to “bear my testimony” . . . are in effect asking me to deal with the most fundamental matters in a shallow, trivial, obvious, and inevitably ineffective way, all the while not noticing that I am already dealing with the LDS cosmology—or my version of it—in everything I do. . . . I will be interested to see what a thoughtful writer [thinks], though I expect I’ll hear much more from the lunatic fringe that believes that a Mormon writer who does not fulfill their personal agenda is somehow corrupt. (p. 13)

The “natter[ing]” “lunatic fringe” that Card discusses reveals a deeper problem that makes it nearly impossible for LDS writers to create qualitative literature that also satisfies their own people. Here, we return to the fear of “all appearance of evil.”

As within many Christian communities, shame and condemnation can easily come at the coat-tails of sin, weakness, injury, doubt, victimization, and even the residual effects of any of these existing in the past; although some of these shames are wholly illogical, only a suspicion may be necessary to incur injury.

The Church’s affirmations that “Ye are therefore commanded to be perfect” (JST Matthew 5:50), “Ye are the light of the world; a city that is set on an hill cannot be hid” (Matthew 5:14, KJV), and “I, the Lord, am bound when ye do what I say; but when ye do not what I say, ye have no promise” (D&C 82:10) only intensify these fears, since they seem to support toxic perfectionism. Other LDS teachings supporting loyalty to Church doctrine and leaders can also be easily misunderstood as condemning unorthodoxy, especially when doctrinal orthodoxy is confused with cultural “orthodoxy.” Taken altogether, LDS culture joins with many Christian traditions in shaming the messiness of human existence as if it were sin.Despite the prolific assertions that Christ exists resolve precisely these issues, these fears of vulnerability and messiness permeate LDS culture. This becomes evident when, upon any mention of a shift in Church policy, some members are guaranteed to shift in their seats right alongside the barometer of “righteousness.” Since the fears are of vulnerability and messiness themselves, they create a taboo against the very vulnerability and messiness that makes for qualitative literature. Although it applies to different degrees in different congregations, this internal taboo enforces (among other issues) a too-strict adherence to cultural orthodoxy within LDS circles that stifles qualitative literature.

Unfortunately, since the fear of public negative opinion restricts LDS conversations to within the LDS community, external taboos create an echo chamber that both reinforces the internal taboos and suffocates creative variety. Again, the internal ability to create qualitative literature is stifled.

Between the external pressure not to publish religious orthodoxy and the internal pressure to publish too-perfect cultural orthodoxy, how is an LDS writer to create qualitative literature for both audiences?

The Protective Cover

Speculative fiction provides the outlet. Speaking of his own science fiction novels, Orson Scott Card states,

As long as I don’t interfere with my own storytelling, I suspect that my works will always reveal my beliefs, both orthodox and unwittingly heretical. And I believe that such expressions of faith, unconsciously placed within a story, are the most honest and also most powerful messages a writer can give. (Card, p. 12)

Card demonstrates this principle beautifully throughout his novel Pastwatch. Jumping from the imagined headspaces of Christopher Columbus, Columbus’s contemporaries, and a group of time-travelers preparing to interfere at the discovery of the Americas, the novel places a myriad of prominently-LDS topics into new contexts; this includes tenacity in faith, the malleability of scripture, loving self-sacrifice, obedience to actual religious teachings over cultural-religious dogma, and the sanctity of human experience through agency.

Additionally, in Shannon Hale’s Dangerous (a more recent science fiction YA novel) alien technology incorporates uniquely-LDS concepts about spirit-matter, bringing up such themes as trusting revelation, the nature of human bodies, and how to put spiritual purpose and carnal nature into proper alignment. Church doctrines are thoroughly explored, but the public eye doesn’t need to see that; and human messiness is showcased, but Latter-day Saint culture doesn’t have to claim ownership of it.

By obscuring both theological principles and vulnerability to human messiness behind the fantastic, speculative fiction creates a buffer between the writer and the audience—a buffer that side-steps all taboos, rewards LDS readers for recognizing the easter eggs of their own doctrine, and provides all readers access to the root humanity behind any good story.

2: Speculative Fiction is a Theologically-Consistent Alternative to Modernism

Encyclopedia Britannica states, “Modernism as a literary movement is typically associated with the period after World War I. The enormity of the war had undermined humankind’s faith in the foundations of Western society and culture, and postwar Modernist literature reflected a sense of disillusionment and fragmentation” (Kuiper, par. 3). This included “a growing alienation incompatible with Victorian morality, optimism, and convention” (Kuiper, par. 2), which often led to the movement’s infamous abandonment of coherent narrative and edifying themes.

While the Modernist movement took America by storm, contemporary Latter-day Saints would have found its tenants to be both old news and wholly incompatible with their theology. The exodus to Utah had already resulted in part from their “undermined . . . faith in the foundations of Western society and culture,” but they had combated “disillusionment and fragmentation” with hope and unity in Christ. Latter-day Saints were already “alienat[ed]” from “Victorian morality, optimism, and convention”—indeed, from the morality and convention of the entire world, especially as they saw it—but they had supplanted incoherence with a firm assertion of divine and absolute truth.

The cultural earthquakes that rocked America at the core were only the second wave for Latter-day Saints; however, America came up with the stark opposite solutions to what the Latter-day Saints had. As a result, when Modernism overtook American literature, the Latter-day Saints found themselves without anyone to talk to—in one way or another, every Modernist work scorned their foundation in Christian hope.

Significantly, J.R.R. Tolkien came out of this same era. Hardly a rejection of “morality, optimism, and convention,” Tolkien’s novels contain coherent narratives, insist on edifying themes, and deeply incorporate the moralism of his own Christian theology. Rather than embracing “disillusionment and fragmentation,” Tolkien created Middle Earth, a world embedded with

Significantly, J.R.R. Tolkien came out of this same era. Hardly a rejection of “morality, optimism, and convention,” Tolkien’s novels contain coherent narratives, insist on edifying themes, and deeply incorporate the moralism of his own Christian theology. Rather than embracing “disillusionment and fragmentation,” Tolkien created Middle Earth, a world embedded with

hope and anchored on central truths—the truths of the world’s internal logic, and the truths of his real-life theological beliefs. It was these qualities, instead of the qualities of Modernism, that came to define the genre J.R.R. Tolkien fathered—the genre of fantasy.

It thus makes obvious sense that Latter-day Saints would eagerly choose fantasy over Modernism. The hope, coherence, and powerful potential for character growth perfectly coincide with the LDS insistence on Christ’s redemption, His divine rule, and our own spiritual progression. The trope of the “chosen hero” agrees with the LDS concept of being “God’s elect,” chosen and tasked with saving the world in “the last days,” while the bildungsroman and personal independence of YA fantasy fit with the LDS concept of continuous growth and self-definition to the end of our mortal lives, well beyond our teenage years.

This logic holds true when we cross the speculative-fiction bridge into science fiction. Card’s and Hale’s books again provide examples of these Tolkien-ian and LDS principles: Pastwatch is essentially an exploration of time-travel as a means for humanity to collectively repent, and Dangerous follows a teenage girl as she learns to step into the LDS-valued roles of hero, leader, and romantic partner.

Additionally, YA posthuman literature—”posthuman” being the branch of science fiction that begs the question What does it mean to be human?—generally coincides with core LDS doctrines by describing humanity’s positive qualities “of empathy, morality, free will, and dignity” (Ostry, p. 236), and YA posthuman literature’s ultimate conclusion that “the choice to become human” (p. 243) makes you human is eerily close to the LDS doctrine of deification: humans are the same species as God, humans can become Gods, and humans become Gods (in the next life) by choosing to act like one, as demonstrated by Jesus Christ and defined by God’s commandments.

Truly, in light of these underlying genre compatibilities, it would be a marvel if Latter-day Saints did not love speculative fiction.

3: Speculative Fiction’s Suspension of Disbelief is Required to Believe LDS Theology

Speculative fiction asks a willing suspension of disbelief for its audience to enjoy the story. Faith in any religion is no different, except that the suspension of disbelief is knowingly applied to the real world. In fact, this is precisely the paradigm that J.R.R. Tolkien (and another friend, Hugo Dyson) used to finally convince now–LDS-favorite C.S. Lewis to accept Christianity—Lewis later said, “Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened” (Gyler, p. 16–17; emphasis in original).

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints actively supports this principle of real-world suspension of disbelief in its doctrine. The Book of Mormon teaches that faith is a “desire to believe” that “work[s] in you, even until,” rather than choosing to “cast it out by your unbelief,” you “believe in a manner that ye can give place for a portion of my words” (Alma 32:27–28, The Book of Mormon).

More significantly, however, the Church takes this real-world suspension of disbelief to the next level. For one thing, Givens notes that “some Mormon doctrine is so unsettling in its transgression of established ways of conceiving reality that is may be more at home in the imagined universes of Card than in journals of theology” (Givens, p. 320).

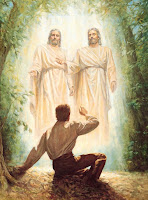

When making this statement, there are certainly several theological points Givens could have had in mind: for perhaps the most ostentatious examples, the assertion of extraterrestrial life (God lives on a planet near the star Kolob and continually creates worlds for His human children to inhabit), the rejection of a metaphysical theology (as evidenced by the belief in spirit-matter), and the practical reality of deification (“As man now is, God once was; as God now is, man may be”).This is to say nothing of the boldly-proclaimed origins of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which only begins with a farm-boy’s literal theophany and the divinely-enabled translation of ancient scripture. After spending one third of a letter to Harper’s magazine detailing the epic potential of the Church’s history, Bernard DeVoto (“the foremost writer and one of the greatest intellectual forces whom Utah has produced in this country” who wrote prolifically about the Church [Fetzer, p. 23] without ever joining it [p. 37]) concludes,

I have the most cordial sympathy for [the] novelists who are trying to compete with the art of omnipotence. . . . Some things exist in nature complete and matchless, and the story of Joseph and his people is one of them, a greater story as you find it than can ever be in fiction. (DeVoto, p. 560)

While absolute acceptance of all the Church’s teachings are not required for baptism, there is immediate pressure to suspend disbelief by how close to home these teachings can come. Regarding the history, DeVoto’s letter came out of a personal trip to Palmyra and the Hill Cumorah in upstate New York, where Joseph Smith retrieved the Gold Plates by angelic guidance, a mere 190 years ago—the location and time are both notably close to home.

As for the doctrines, many of them have immediate and practical applications that encompass Latter-day Saint daily living. Although aspects of LDS culture conflict with Church theology (as demonstrated), it is still not inaccurate to say that the Church fully intends to create “the original, the ultimate, the eternal culture that comes from the gospel of Jesus Christ” (Jackson, last paragraph). This means “chang[ing] the way we love, think, serve, spend our time, treat [one another], teach our children, and even care for our bodies” (Nelson, par. 5)—in the immediate present.

This close-to-home pressure calls for active members of the Church to willingly suspend their disbelief about the Church’s epic doctrines every moment of their lives. This is not to say that every active member whole-heartedly believes every teaching, but rather that every sincere member whole-heartedly desires to believe truth (“truth is knowledge of things as they are, and as they were, and as they are to come” [D&C 93:24]), however radical that truth may be. This desire fosters daily practice suspending disbelief; without, as was noted in the above discussion on Modernism, suspending belief either.

It is thus to be expected that sincere Latter-day Saints develop an affinity for speculative fiction. As members learn and learn to believe more about the fantastical theologies of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—which is certainly more than a life-long endeavor—the subjects they suspend disbelief on invariably change.

Over time, such continued shifts create an affinity for flexibility; a flexibility that is perfectly suited to consuming and creating a variety of speculative fiction stories, each with its own fantastical world-building and unbelievable events that ask, paradoxically, to be believed anyway. Truly, speculative fiction’s suspension of disbelief matches perfectly with the Latter-day Saint habit of shelving the question “What is not true?” to ask first “What could be true?”

Conclusion

When Orson Whitney stated, “We will yet have Miltons and Shakespeares of our own,” he continued,

God’s ammunition is not exhausted. His brightest spirits are held in reserve for the latter times. In God’s name and by his help we will build up a literature whose top shall touch heaven, though its foundations may now be low in earth. Let the smile of derision wreathe the face of scorn; let the frown of hatred darken the brow of bigotry. . . . Eternity is before us. (par. 18, 19)

Improvements should be made to Latter-day Saint culture that would allow all LDS literature to more readily flourish. However, it still stands that speculative fiction allows the community a resolution of internal and external taboos, provides a theologically-consistent alternative to Modernism, and employs a suspension of disbelief that the Church’s doctrine gives its members a noted affinity for. Each of these three qualities could stand on its own, but taken together they clearly demonstrate why members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints would have a particular passion for speculative fiction.

Sources Cited

Bloom, Harold. The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992, 82, 127. This is as Givens cited Bloom in People of Paradox: A History of Mormon Culture; I was not able to find the source.

Card, Orson Scott. “LETTERS,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, vol. 18, no. 2, 1985, pp. 4–13. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/45227954.

DeVoto, Bernard. “Vacation,” Harper’s Magazine, Internet Archive, Harper & Brothers, 1 Jan. 1970, archive.org/details/harpersmagazine177junalde/page/558/mode/2up.

England, Eugene. “Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects,” http://mldb.byu.edu/progress.htm. As cited on the website: “Editor’s Note: This is the single most comprehensive essay on the history of Mormon Literature, originally appearing with the same title in David J. Whittaker, ed., Mormon Americana: A Guide to Sources and Collections in the United States. (Provo, Utah: BYU Studies, 1995): 455-505. It has been adapted slightly from its print version (with some updated bibliographic material and the addition of weblinks).”

---. “Pastwatch: The Redemption of Orson Scott Card,” mldb.byu.edu/eng-osc.htm. As cited on the website: “This paper was first presented at ‘Life, the Universe, & Everything XV: An Annual Symposium on the Impact of Science Fiction and Fantasy,’ Provo, Utah, February 28, 1997. It has been edited by symposium staff and will be published in Steve Setzer and Marny K. Parkin, eds., Deep Thoughts: Proceedings of Life, the Universe, & Everything XV, February 27- March 1, 1997 (Provo, Utah: LTU&E, forthcoming).”

Fetzer, Leland A. “Bernard DeVoto and the Mormon Tradition,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, University of Illinois Press, Autumn-Winter 1971, Vol. 6, No. 3/4 (Autumn-Winter 1971), pp. 23-38, https://www.jstor.org/stable/45224224.

Geary, Edward A. “The Poetics of Provincialism: Mormon Regional Fiction,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, vol. 11, no. 2, 1978, pp. 15–24. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/45224656.

Givens, Terryl L. “Chapter 15: ‘To the Fringes of Faith,’” People of Paradox: A History of Mormon Culture, Oxford Univ. Press, 2012, pp. 285–324.

Glyer, Diana Pavlac. Bandersnatch: C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and the Creative Collaboration of the Inklings, The Kent State University Press, 2016, ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/byu/detail.action?docID=4186508.

Jackson, William K. “The Culture of Christ,” Ensign, November 2020, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2020/10/27jackson?lang=eng.

Kuiper, Kathleen. “Modernism,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 24 Mar. 2020, https://www.britannica.com/art/Modernism-art.

Nelson, Russell M. “We Can Do Better and Be Better,” Ensign, May 2019, www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2019/04/36nelson?lang=eng.

Ostry, Elaine “‘Is He Still Human? Are You?’: Young Adult Science Fiction in the Posthuman Age,” The Lion and the Unicorn, Volume 28, Number 2, April 2004, pp. 222-246, doi:10.1353/uni.2004.0024.

Paulson, Michael. “Faith and Good Works,” Boston.com, The Boston Globe, 1 Mar. 2009, archive.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2009/03/01/faith_and_good_works/?page=full.

Religion News Blog. “Utahns Devour and Write a Galaxy of Fantasy Fiction,” Religion News Blog, 27 Aug. 2013, www.religionnewsblog.com/4122/utahns-devour-and-write-a-galaxy-of-fantasy-fiction. As cited in Gives’s bibliography, http://www.rednova.com/news/space/17639/utahns_devour_and_write_a_galaxy_of_fantasy_fiction.

Whitney, Orson F. “Home Literature,” mldb.byu.edu/homelit.htm. As cited on the webpage: “First delivered as a speech by Bishop Orson F. Whitney, at the Y.M.M.I.A. Conference, June 3, 1888, and subsequently published July, 1888 in The Contributor.”

Image Attributions

1) Cover art of Dangerous by Shannon Hale, borrowed from https://shannonhale.fandom.com/wiki/Dangerous.

2) Cover art of the first single-volume edition (1968) of The Lord of the Rings, borrowed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:First_Single_Volume_Edition_of_The_Lord_of_the_Rings.gif.

3) The First Vision, by Del Parson, borrowed from https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/media/image/the-first-vision-fe5db8d?lang=eng.

No comments:

Post a Comment